The Rhythm of Prostopinije

Most music we hear has a discernible, regular rhythm – a "beat" – and a meter that divides this rhythm up into regular groups of beats, with a regular accent expected at the start of each group. Like poetry, the music may be divided up into verses or stanzas which repeat this rhythm exactly. When this music is written down, bar lines define where the accents occur at the start of each phrase, and the first note of a measure immediately follows the last note of the previous one.

In prostopinije, the basic rhythm is that of "free" speech (that is, prose and not poetry). Accents fall where a syllable is accented within a word, or a word within a phrase or sentence. Unlike the Greek liturgical music from which it arose, Slavic liturgical chant assumes that phrases may be longer or shorter, and have a few accents or many. This affects the musical "sound" of prostopinije in profound ways.

The rhythm of speech

In some languages, such as French, syllables are spoken at a regular pace, regardless of accent or stress. English and Church Slavonic, on the other hand, are stress-timed languages: it is the accents or stresses in a sentence that fall at regular intervals. This is not exact, of course, and the syllables may be slower at ends of phrases, or when something particularly important or exacting is being said.

But in general, English speech can be said to proceed two or three syllables at a time; it slows down when several accented syllables are spoken in a row (think "big red ball") and speeds up when there are many unaccented syllables between accents (think "beáutifully entertáining"). English prose derives much of its charm from not falling into a regular duple rhythm ("one two, one two") or triple rhythm ("one two three, one two three"), but alternating between the two.

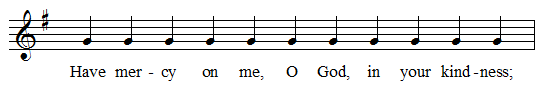

Prostopinije shares these characteristics. Most chant melodies accommodate either longer or shorter liturgical texts by "stretching" in the middle of most phrases. These syllables are sung in the rhythm of formal (that is, careful) speech, so that the quarter notes in the following passage are not all the same length:

There are also small tricks that we use naturally when speaking or singing: for example, we can indicate an accent or stress by raising pitch slightly, or by beginning at a slightly lower pitch and then raising it over the course of a syllable. Sometimes an accented syllable may be spoken or sung slightly louder, or with a change in timbre that says "pay attention here." All of these methods can be used when speaking or singing; the only trick is to use them well, without over-emphasizing them. (Doing so can sound overly precise or "picky", as if you don't trust to hearer to understand what you are saying!)

In practice, we notate plain chant by using ordinary half notes, quarter notes and eighth notes to show whether a syllable or pitch is sung normally, quickly, or very quickly, and these differences are entirely relative, based on the sense of what is being said, and the spirit of the melody. When more than three syllables are sung on a pitch, we usually write them under a "slashed note", a whole note with two bars on each side:

This means that the text under the slashed note is sung to the rhythm of ordinary, formal speech. Even when an intonation (beginning of a phrase) or cadence (end of a phrase) are written with ordinary notes, the cantor needs to adjust their rhythm slightly to match the sound and pacing of the words, the meaning of the entire phrase, and how it fits into the entire hymn.

Exercise: Try singing a psalm such as Psalm 66 on a single pitch, making sure that the words are clear and you are singing them in approximately the same rhythm that you would read them aloud. If you haven't read aloud for a long time, make time to practice by reading to children or other adults.

The bar line

In plain chant, the bar line does not group music into "measures" with the same number of beats; it divides the hymn into phrases, each of which can be sung on one breath, and which make sense together. Between each phrase there is a break in the singing, which can differ from the slightest silence to a definite pause, depending on the meaning of the words. For example, if two phrases form one meaning between them, there may be almost no pause as all, and the cantor should quickly grab a breath. Consider the kontakion of Pascha:

Between the first two phrases ("Rising from the grave, you raised the dead."), there should be hardly any break at all, since the first phrase cannot stand on its own; if you were reading aloud and stopped at the bar line, it would sound wrong. Wherever a period occurs in the kontakion, there can be a noticeable pause (one "beat") at the bar line, with a shorter pause at the comma after Adam is mentioned. Again, in the final sentence, there should be no pause at all between the two phrases, just a quick breath between beats..

The entire hymn should be sung in the rhythm of normal, careful speech, except for the end of each phrase (the "cadence"), where half notes or dotted half notes instruct you to hold a syllable for two or three times its normal length. The overall tempo should not slow down at these cadences; the overall "beat" of the music should continue, slowing down only at the very end of a hymn or group of hymns.

Exercise: Spend some time listening to plain chant, in church or in recordings, and pay attention to the effect of different kinds of pauses between phrases. What sounds appropriate, and clarifies the meaning of the text? Which pauses sound too long or too short?

The size of the pause at a bar line may also be shortened if the previous phrase ends with a single unstressed syllable, or the next phrase begins with one. When this happens, the time it takes to sing the unaccented syllable may be "stolen" from the pause at the bar line. This comes with practice, and careful listening.

Processional rhythm

As mentioned above, most plain chant is sung to the rhythm of free speech, with syllables speeding up and slowing down to match the accents and stresses. But for certain melodies, the "stretching" part of each phrase is sung as if it were regular quarter notes or half notes, even if a slashed note is used:

- the tone 2 troparion melody ("The noble Joseph took down your most pure body from the cross...") (listen)

- the tone 5 troparion melody (listen)

- the tone 8 troparion melody (listen)

These a processional melodies, and intended to be sung to a regular walking rhythm. For example, the Tone 2 troparion melody is used during the procession with Christ's burial shroud on Great and Holy Friday. In these melodies, the entire hymn should be sung to a regular beat, and volume or timbre changes should be used to mark the accents and stresses in the text being sung. In all three melodies, quicker notes at the end of each phrase or every other phrase add rhythmic interest, while keeping the same overall "beat."

Exercise: Listen to the three melodies above and make sure you can identify the sound of a processional rhythm.

Remember, the processional rhythm is used in these melodies even when a slashed note is put over the text. Also, note that when these melodies are written as sequences of half notes, each half note gets one "beat" rather than two. (Musicians call this "cut time.")

Composed rhythms

Not all the prostopinije melodies comes from the older plain chant tradition; some melodies are borrowed from the folk song tradition, or composed from scratch using the musical standards of the time. These melodies may have the exactly repeated patterns of the verses of Western-style hymns, where every verse is sung to the exact same melody.

The principal example of this in the Divine Liturgies book is the hymn, A New Commandment, on the last page of the book. Here, the bar line does not represent any pause at all, but divides the music up into measures of four quarter notes each ("4/4 time").

There is also composed melodies which are drawn from the same folk song tradition, but adapted for plain chant use by reorganizing the music into phrases of different numbers of syllables as needed. This is the case, for example, with the various Cherubic Hymns on pages 42-49 (some of which use melodies borrowed from Marian or feast-day para-liturgical hymns) and certain other hymns sung at the Divine Liturgy. When singing these melodies, the cantor has the option of treating the bar line as a brief pause, or of singing "through" the bar line to keep the beat.

Tempo

The tempo (speed) of prostopinije singing has to be adjusted to fit the needs of the service. A melody like Tone 2 troparion may be sung in a slow and stately fashion on Great and Holy Friday, and with great life and vitality two weeks later on the Sunday of the Myrrh-bearers. Furthermore, even within a single service, a good cantor may need to speed up or slow down the singing slightly to match the actions of the priest or deacon, the length of the line for Holy Communion, and so on. See Leadership.

It is safe to say, however, than in most parishes, plain chant is sung too slowly, and with a heaviness that runs counter to good congregational singing. This is due in part to a belief that singing slowly (or even ponderously) is more "churchly", and also because instructional tapes prepared in the late 1970's and early 1980's included singing that was intentionally slow, in the hope that this would facilitate learning. Instead, cantors copied the slow tempo.

A reminder: if plain chant is sung so that the pulse is on a half-note rhythm, rather than on every quarter, this adds a great deal of life and interest to the singing; pairs of quarter notes or groups of four eighth notes suddenly acquire a vigor they lack when sung too slowly.

Recommended Reading

- Saintsbury, George. A History of English Prose Rhythm.

(London: McMillian, 1922).

Still one of the best books available about the mechanics of English prose speech and its rhythm.